Each time I’ve had a new novel come out, I’ve done an article about the technology in the previous novel. Here are two of my prior posts:

Now that The Turing Exception is available, it is time to cover the tech in The Last Firewall.

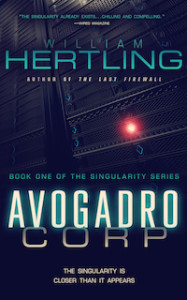

As I’ve written about elsewhere, my books are set at ten year intervals, starting with Avogadro Corp in 2015 (gulp!) and The Turing Exception in 2045. So The Last Firewall is set in 2035. For this sort of timeframe, I extrapolate based on underlying technology trends. With that, let’s get into the tech.

Neural implants

If you recall, I toyed with the idea of a neural implant in the epilogue to Avogadro Corp. That was done for theatrical reasons, but I don’t consider them feasible in the current day, in the way that they’re envisioned in the books.

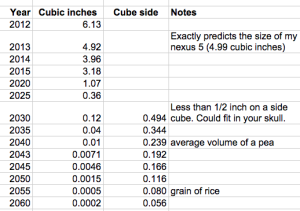

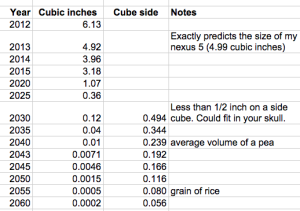

Extrapolated computer sizes through 2060

I didn’t anticipate writing about neural implants at all. But as I looked at various charts of trends, one that stood out was the physical size of computers. If computers kept decreasing in size at their current rate, then an entire computer, including the processor, memory, storage, power supply and input/output devices would be small enough to implant in your head.

What does it mean to have a power supply for a computer in your head? I don’t know. How about an input/output device? Obviously I don’t expect a microscopic keyboard. I expect that some sort of appropriate technology will be invented. Like trends in bandwidth and CPU speeds, we can’t know exactly what innovations will get us there, but the trends themselves are very consistent.

For an implant, the logical input and output is your mind, in the form of tapping into neural signaling. The implication is that information can be added, subtracted, or modified in what you see, hear, smell, and physically feel.

Terminator HUD

At the most basic, this could involve “screens” superimposed over your vision, so that you could watch a movie or surf a website without the use of an external display. Information can also be displayed mixed with your normal visual data. There’s a scene where Leon goes to work in the institution, and anytime he focuses on anyone, a status bubble appears above their head explaining whether they’re available and what they’re working on.

Similarly, information can be read from neurons, so that the user might imagine manipulating whatever’s represented visually, and the implant can sense this and react accordingly.

Although the novel doesn’t go into it, there’s a training period after someone gets an implant. The training starts with observing a series of photographs on an external display. The implant monitors neural activities, and gradually learns which neurons are responsible for what in a given person’s brain. Later training would ask the user to attempt to interact with projected content, while neural activity is again read.

My expectation is that each person develops their own unique way of interacting with their implant, but there are many conventions in common. Focusing on a mental image of a particular person (or if an image can’t be formed, then to imagine their name printed on paper) would bring up options for interacting with them, as an example.

People with implants can have video calls. The ideal way is still with a video camera of some kind, but it’s not strictly necessary. A neural implant will gradually train itself, comparing neural signaling with external video feedback, to determine what a person looks like, correlating neural signals with facial expressions, until it can build up a reasonable facsimile of a person. Once that point is reached, a reasonable quality video stream can be created on the fly using residual self-image.

Such a video stream can be manipulated however, to suppress emotional giveaways, if the user desires.

Cochlear implants, mind-controlled robotic arms and the DARPA cortical modem convince me that this is one area of technology where we’re definitely on track. I feel highly confident we’ll see implants like those described in The Last Firewall, in roughly this timeframe (2030s). In fact, I’m more confident about this than I am in strong AI.

Cat’s Implant

Catherine Matthews has a neural implant she received as a child. It was primarily designed to suppress her epileptic seizures by acting as a form of active noise cancellation for synchronous neuronal activity.

However, Catherine also has a number of special abilities that most people do not have: the ability to manipulate the net on par with or even exceeding the abilities of AI. Why does she have this ability?

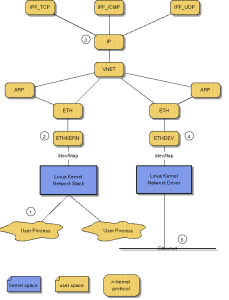

The inspiration for this came from my time as a graduate student studying computer networking. Along with other folks at the University of Arizona, studying under Professor Larry Peterson, we developed object-oriented network protocol implementations on a framework called x-kernel.

These days we pretty much all have root access on our own computers, but back in the early 90s in a computer science lab, most of us did not.

Because we did not have root access on the computers we used as students, we were restricted to running x-kernel in user mode. This means that instead of our network protocols running on top of ethernet, we were running on top of IP. In effect, we run a stack that looked like TCP/IP/IP. In effect, we could simulate network traffic between two different machines, but I couldn’t actually interact with non-x-kernel protocol stacks on other machines.

In 1994 or so, I ported x-kernel to Linux. Finally I was running x-kernel on a box that I had root access on. Using raw socket mode on Unix, I could run x-kernel user-mode implementations of protocols and interact with network services on other machines. All sorts of graduate school hijinks ensued. (Famously we’d use ICMP network unreachable messages to kick all the computers in the school off the network when we wanted to run protocol performance tests. It would force everyone off the network for about 30 seconds, and you could get artificially high performance numbers.)

In the future depicted by the Singularity series, one of the mechanisms used to ensure that AI do not run amok is that they run in something akin to a virtualization layer above the hardware, which prevents them from doing many things, and allows them to be monitored. Similarly, people with implants do not have access to the lowest layers of hardware either.

But Cat does. Her medical-grade implant predates the standardized implants created later. So she has the ability to send and receive network packets that most other people and AI do not. From this stems her unique abilities to manipulate the network.

Mix into this the fact that she’s had her implant since childhood, and that she routinely practices meditation and qi gong (which changes the way our brains work), and you get someone who can do more than other people.

Mix into this the fact that she’s had her implant since childhood, and that she routinely practices meditation and qi gong (which changes the way our brains work), and you get someone who can do more than other people.

All that being said, this is science fiction, and there’s plenty of handwavium going on here, but there is some general basis for the notion of being able to do more with her neural implant.

This post has gone on pretty long, so I think I’ll call it quits here. In the next post I’ll talk about transportation and employment in 2035.

The first book I want to mention is Pandora’s Brain by Calum Chace. I first met Calum in a roundtable discussion about the risks of artificial intelligence, and he was kind enough to share an early draft of Pandora’s Brain which I devoured over the course of a day or two. It immediately struck me as a tour de force of virtually all singularity-related concepts, from mind uploading to artificial intelligence to simulated universe theory. I had a blast reading it, and if you’re a singularity geek like I am, I think you’ll enjoy it too. It is the first in a series, and I’m looking forward to reading the rest and learning where the story goes.

The first book I want to mention is Pandora’s Brain by Calum Chace. I first met Calum in a roundtable discussion about the risks of artificial intelligence, and he was kind enough to share an early draft of Pandora’s Brain which I devoured over the course of a day or two. It immediately struck me as a tour de force of virtually all singularity-related concepts, from mind uploading to artificial intelligence to simulated universe theory. I had a blast reading it, and if you’re a singularity geek like I am, I think you’ll enjoy it too. It is the first in a series, and I’m looking forward to reading the rest and learning where the story goes. The second book is Superposition by David Walton. I received an advance review copy of Superposition from Pyr. It was pitched as “a quantum physics murder mystery, a fast-paced mind bender with the same feel as films like Inception or Minority Report. The story centers around a technology in which some of the weird effects that apply to particles at a quantum scale can be made to affect everyday objects, such as automobiles or guns or people.” I had had a blast reading it. Very fun, and you’ll learn a bit about quantum physics in the process. We’re in for some weird times if we ever harness quantum effects on a macro scale.

The second book is Superposition by David Walton. I received an advance review copy of Superposition from Pyr. It was pitched as “a quantum physics murder mystery, a fast-paced mind bender with the same feel as films like Inception or Minority Report. The story centers around a technology in which some of the weird effects that apply to particles at a quantum scale can be made to affect everyday objects, such as automobiles or guns or people.” I had had a blast reading it. Very fun, and you’ll learn a bit about quantum physics in the process. We’re in for some weird times if we ever harness quantum effects on a macro scale. Finally, I’ve been looking forward to Zeroboxer by Fonda Lee for months. Fonda is a local Portland author, and I attended the launch last night, where she completely rocked the reading. I just started Zeroboxer, and so far I’m enjoying the book very much. Imagine zero gravity martial arts combat. If that sounds as awesome to you as it does to me, then go buy the book immediately. 🙂

Finally, I’ve been looking forward to Zeroboxer by Fonda Lee for months. Fonda is a local Portland author, and I attended the launch last night, where she completely rocked the reading. I just started Zeroboxer, and so far I’m enjoying the book very much. Imagine zero gravity martial arts combat. If that sounds as awesome to you as it does to me, then go buy the book immediately. 🙂

![Pageflex Persona [document: PRS0000030_00039]](http://www.williamhertling.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/wilted_broccoli_kids-300x196.jpg)